Professor Gibbern's preparation

The Banishment, Andrei Zvyagintsev’s second feature-length motion picture after triumphing in Venice with The Return (2003), was received coldly by the audience. After the first screenings, bewilderment reigned even among “advanced” cinema enthusiasts. Some applauded languidly, some grumbled discontentedly, and when cineastes read slashing reviews by renowned film experts, a torrent of criticism pounced on Zvyagintsev like tsunami on the province of Aceh. It seemed that curses and swearing would sweep yesterday’s favorite down to the ocean of oblivion, and Andrei would drown there along with Aleksandr Baluyev, Konstantin Lavronenko, and Maria Bonnevie. Those who only yesterday had raved about The Return regretted their past admiration: as they said, “we were “bought” all for nothing at the time”. Those who had silently swallowed the success of The Return, felt relief at last by stating that “the movie is total shit.”

Yekaterina Barabash argued that Zvyagintsev had invented “spiritual glamor”: merciless in its form and meaningless in its content. Yelena Ardabatskaya noted that it had been a difficult viewing experience since The Banishment has nothing at all in it: no people, no scents, only Emptiness. Roman Volobuyev, who at first confined himself mostly to sneering, finally succumbed and began to speak his mind. According to him, even Mikhalkov, now an object of scorn, “is a complex personality, while Zvyagintsev is a single-layered structure; he is a good professional director, at the level of an average American TV series maker, who makes films about things he does not give a damn about – and out of mercenary motives at that, and because he works not in the world of ‘My Perfect Nanny’ but in Russian, kind of, spirituality, his indifference and the fact that he knows nothing about those abstruse things that he depicts in his movies is the most terrible thing.” Even peacefully disposed Sam Klebanov complained, “It seems as if it is repeatedly suggested that we should think about the meaning of all those religious parallels. Perhaps, we did not think well enough, but somehow we have not thought up anything.” I am not going to list all the complaints and accusations of displeased cinema experts and female viewers; I am just going to say that the criticism against The Banishment boils down to three things: 1) The indeterminate time and place of the film; Let us figure them out one by one. Time and Place Perhaps, in some other film the soft slopes, jade crockery and flecks of dust in sunbeams would be hurrahed, but the sophisticated aesthetics of The Banishment repelled the audience. The mannerism of the mise-en-scènes, the scenic splendors in conjunction with the director’s maniacal determination to drive all markers of time out of the shot built a wall of incomprehension between the audience and the movie. It appeared to many that it was nameless ghosts, not living people, that were wandering in empty rooms and lonely copses, that the director tried to disguise the poverty of the content behind the beauty of the shot. Is that the case? Let us look at the situation from another angle.

Have you ever tried to recount a dream? If you have, you certainly experienced a sort of frustration because it is impossible to communicate these feelings that only you can comprehend. Well, why should we limit ourselves to speaking about dreams? Even in our day life there are such breakdowns, such overflows of feelings, such “psychological spaces” that cannot be told about because words fail us. Sometimes poetry can help, sometimes music, and sometimes cinema. There is an expression “dream cinema.” At times this kind of cinema opens such layers of memory, gives such feelings that can be both more vivid and more exuberant than, for instance, your reminiscences about your first love or your visit to China. Alexei German’s film Khrustalyov, mashinu! [Khrustaliov, My Car!] is regarded as a classic example of dream cinema. I cannot speak for others, but The Banishment reminded me of my experience of my first day in Madrid, which was a prominent, say, rough experience at first, but completely forgotten afterwards. For some reason, it is the first days in a new place that always stand apart. Of course, everyone has one’s own psychological reality. It stands to reason that there will always be someone left indifferent by the aesthetics of the film, and this is right. Look at cinema from that angle, and maybe some other film will awake something in you which cannot be expressed in words. The opinion that cinema is the closest to the world of dreams is common among film experts, and I can only agree with that opinion. The Banishment was filmed in southern Moldova, 5 kilometers away from the city of Vulcanesti. I do not know where precisely in Moldova Hare over the Abyss was shot, but as soon as I saw the landscapes of The Banishment I immediately remembered Keosayan’s picture. Such is Moldova, beautiful and sentimental! So, any “namelessness” is quite a relative thing. The important thing is the breadth of vision. Artificiality of the Plot? Can we say that the plot of The Banishment is artificial? It depends on how you look at it. Indeed, at first sight, the harmonious story about adultery, pregnancy, about relationships between a man and a woman collapses like a house of cards at the end of the film. And the blame is to be attributed to the “sacrifice” of the heroine. Female viewers were especially outraged by the fact that the character of Vera is phony throughout, that instead of a woman Zvyagintsev presented a phantom, a masculine perception of a woman. It is funny that a considerable difference is observed between the male and female assessments of The Banishment at IMDB. Whereas women assessed the film at 6.4 on the average, men voted it an 8.0. This does not happen often. But the thing is, I am convinced that the family drama, the outline of events, is only the threshold of the deeper layers of the film. In this context, the absurdity of Vera’s actions, her adultery, her allusions and sacrificial abortion acquires an entirely different approach. It is interesting to note that with the widespread introduction of the DNA test, the problem of adultery became of unprecedented importance in society. In cinema came Cannes laureate Cristian Mungiu’s 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days and then Zvyagintsev’s The Banishment, both of which sparked fierce clashes in online forums with regard to adulteries and related abortions. But in The Banishment the abortion is not the subject, but only the cause, of the dispute. The film is not about the abortion; then what is it about? On November 21, 2006 Rossiyskaya Gazeta published an interview with Andrei Zvyagintsev. Answering correspondent Valeriy Kichin’s question concerning The Banishment the director says: Zvyagintsev: …In general, it should be said that the character is not at all important to me as a personage or social type, but as a carrier of certain ideas. Not as an individual, but as a function embodied in that actor or actress. Valeriy Kichin: In other words, you understand a film as a working model of life? Zvyagintsev: Yes, as life arrangement. Not at the popular level, but at the metaphysical, perhaps, even at the mystical level. The same thing happened in The Return: there, the father was not simply, and not only a concrete person, but also a certain function, the personification of some concept. And the children too. That’s just the way I am: I begin to get interested if I don’t so much discover the hero as a character as find a clue to his idea. The beauty of the world is not at all embodied through disgraceful fights in the world of people who live by their emotions, greed and passions. It is expressed through the battle in the world of ideas. There, this battle is never-ending and beautiful. These words immediately turn everything upside down. A conscientious viewing of the film will allow you to see a story with carefully arranged prompts behind the heap of words and events from the very first shot. Zvyagintsev did not want to perplex the viewer at all. On the contrary, he shows his cards by both the film itself and direct allusions in his interview. It turns out that an enormous world opens up behind the outline of events, where all puzzles turn into solutions. So, what is this film about? Content and Meaning The reviews of The Banishment repeatedly mentioned its numerous allusions, quotations, metaphors; but in those reviews all allusions, hints, quotations spilled like beads on the floor. It seemed as if the plot lived its separate life, whereas the quotations lay about separately. Meanwhile, a careful and slow viewing of the film will change the viewer’s attitude to it. 0 minutes 0 seconds – 4 minutes 18 seconds First scene: A spreading tree grows by a country road between a tilled soil and a field until a car appears on the horizon. The car rushes along the country road, enveloping this tree in clouds of dust.

It then rushes along a highway between a forest and a field passing out of sight three times.

The car enters an industrial suburb of a city. Clouds of smoke pour from chimney stacks. It is sprinkling and getting dark. Note that at the beginning the car moves in open space; now it moves either between factory walls or between a canal and a string of buildings, strictly confined.

The car can turn neither to the right nor the left. In spite of anxious blinking of the traffic lights, the car moves ahead determinedly. At this moment a train blocks the way. That’s it. The car stops. A shower begins. The driver uses the pause to bandage his blooded hand, but as soon as the crossing gate rises, he drives ahead. At last the car drives up to a house in the dead of night, that is, it enters the city in the daytime and drives up to the house at night! At night! What the hell is this megalopolis that you have to drive through from morning till night?! This is not Tokyo or Moscow, after all! There are no traffic jams.

How should we understand this? From the first seconds of the film the director begins playing a frightful, inconceivable game with the viewer, but almost nobody notices it! The ordinary, worldly worldview is left behind, and we are falling, falling, falling into a dream, a myth, some metaphysical universe. And here, in the world behind the looking glass, the country behind the eyelashes, everything becomes suddenly clear. So, a car, a field, a forest, and a city. There it is! This is a direct paraphrase of the history of the Civilization, or, to be more precise, a historical narrative with its traditional division of the time into three periods: the Ancient World (field), the Middle Ages (forest) and Modernity (city). From this angle, The Road becomes the Metahistory in itself, and the Tree becomes a symbol of Eden or the prehistoric Paradise. That’s that! “That’s all, babies, that’s all, chickens, get off, here we are.” The Banishment begins with the imposition of a sentence, with a peculiar version of The Decline of the West from Zvyagintsev. A thousand-year history is compressed to four minutes and a half. Having started its movement in the blooming Paradise, civilization ended it in impenetrable gloom: there is no further way. No further way? And in general? Is there any way out? Is there any alternative to the onward movement in the “Car”? 4 minutes 18 second – 9 minutes 31 seconds As it turns out, the driver’s name is Mark, and he has come to his younger brother Alex seeking refuge. The name Mark is derived from the Latin Marcus, which means “hammer, sledge-hammer.” Bloodstained Mark needs rest and a night’s lodging. And not only this; he needs help, which is provided by Alex, as Mark declines the offer to call a doctor. Alex extracts a bullet from Mark’s shoulder and then washes off the blood. As it will turn out later, the refusal to bring in a doctor proves to be a prudent step.

Throughout the film Mark is an example of unparalleled courage and self-renunciation. The most courageous and heroic character, a perpetual wanderer used to relying only on himself, Mark proves the most vulnerable as well. While Vera goes to death of her own volition, Mark fades away before our eyes. Wounded, exhausted and sick, Mark dies of a heart attack. The younger brother is not such a straightforward character. On the one hand, sullen and taciturn Alex resembles his brother in his “self-standing”, striving to decide everything on his own. But on the other hand, Alex constantly hesitates. He is not a “hammer.” The name Alexander is derived from the Greek words Alex (“protector”) and Andros (“man”). Alex is in no hurry to make decisions. His ability to hesitate, to pass his decisions through his doubts—that is to say, his tendency to contemplate—turns out to be a colossal advantage for him. Alex will stay alive. So, Mark finds an abode at his brother’s place. At this time Alex tells him that a certain Robert promised him a two-month job, after which he is going to visit his parents home. In other words, while Mark’s way takes him to the city, Alex’s journey is from the city to the place where Mark has just come from. The brothers differ from each other even by this insignificant detail, but the principal difference between Alex and Mark is that the former has Vera. 9 minutes 31 seconds – 11 minutes 49 seconds Alex’s wife, Vera, is an absolutely enigmatic human being. Vera is almost always subordinate and lacks initiative. Her fate seems to be suffering and tears. It is Vera, however, who is at the center of the story; she is the catalyst of the drama. Her contradictory actions break the plot of the movie,and her monologue about children and parents totally perplexes the viewer. The Russian word vera (“faith”) is not just a woman’s name. What if Vera is not only Alex’s wife, not only the mother of his children, but also vera (“faith”), that is, “conviction”, “belief in something”, a religious category? How will she fit in the plot structure in that case? Let us think.

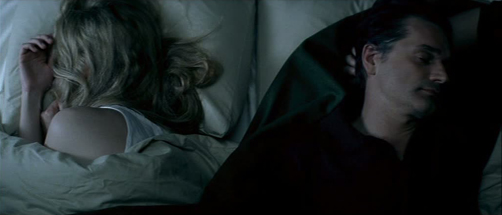

Some time later Vera and Alex travel by train. They go not by themselves, but with their children, a boy and a girl. The son’s name is Kir, the daughter’s Eva. In spite of the fact that Alex has vera (“faith”), it exists separately, so to speak, as if in a parallel world. Despite their wedding rings, an abyss of estrangement has opened between them. They are separate both in their marriage bed and in the train compartment. What is more, it is not only they who sit separately. Alex sits with the son, and Vera sit with the daughter. In the course of the film Zvyagintsev repeatedly separates and estranges male and female protagonists.

It is evident even by the structure of the mise-en-scène in the train compartment: Vera’s relationship with the male half of the family is tragically broken, but her relationship with her daughter Eva is happily established.

As soon as the train approaches the destination, the sunshine lightens Vera as a sign, as a divine testimony. Vera’s face is illuminated with a smile.

With maniacal persistence the director likens the city to the Kingdom of Darkness, and the surroundings of the House of the Father to a Light Paradise. The train arrives at the destination and the family disembarks onto the platform. Even the shape of the station hints at different directionality of their worlds: one arrow points to the left, and the other to the right. The following episode, though barely noticeable, is important: Vera lingers with her things, and Alex and Kir go ahead. Eva stays with Vera, but then dashes after her father and brother. And for a reason, as it will turn out.

11 minutes 53 seconds – 19 minutes 37 seconds After leaving the city, the family returns to the house of Alex’s father. Why there? What is special about it? If you look carefully, you will notice that the house is separated from the outside world by a deep ravine. The ravine is covered with a wooden bridge. Before the bridge, there is a telegraph pole.

All of a sudden, this telegraph pole, or more exactly, its cross-shaped top starts hitting the eye literally from any camera angle. Watch the film carefully. The cross, inconspicuous at first, obtrusively finds its way to the center of the frame. It is viewed by Georgy and Victor, Alex and Kir. It can be seen from any window, from any room. There is a wide cross on the house façade. In addition, the camera lingers on cross-shaped rafters, window sashes and door beams that form crosses.

The testimony is obvious and unequivocal: the paternal home, the family cradle is nothing else than the House of God, the Church or Christianity as a whole. There, beyond the ravine, there are cars, flocks of sheep pasturing; but here is the House of God as the place of last hope. The House of God is consigned to oblivion by people in exactly the same way as Christianity is almost everywhere in modern-day Europe. Only the extinguished hearth and gray ash are left.

Nevertheless, Alex, Vera, Kir and Eva begin to adapt to it, to settle in its rooms. The shutters are opened, fire burns in the hearth again, and light illuminates dark corners. Is seems that the forgotten temple will be reanimated. Will it? Something uneasy floats in the air from the first minutes. Leafing through a book, Kir opens to an enigmatic reproduction showing three occult, folkloric figures. Then Kir asks Alex about the strange odor that is present in the house, but receives no answer. Crucial significance is attached to the symbolism of water. Water as a symbol of life is used often in esoteric literature, painting and cinema. In The Banishment, water, or rather its absence, the thirst for water, conveys a sinister meaning. On the way home Eva says that she is thirsty. Then a certain spring located in the walnut garden becomes the focal point of the conversation between Kir and Alex. Alex answers that they can go to the garden, that is, to the spring, only after bathing. Bathing or ablution acts here as an allusion to the Baptism of Christ; that is to say, one can get to the garden or Eden only after being baptized.

The omnipresent cross, ablution, ravine, the House of the Father are only the beginning in the endless sting of biblical, historical and Christian allusions, which not only stick out everywhere, but also fit in a clear sequence, forming several storylines. Each storyline—biblical, metahistorical, familial—affects and depends on the other lines, and each episode is reflected in mirrors of different conceptual levels. And the most important thing is that it is not the parable that explains reality, but reality that explains the parable. In an interview with Kseniya Golubovich, Zvyagintsev said, “Few people think about the fact that a ‘myth,’ a ‘pattern,’ some turn which has been known to humankind for millions of years, underlies every event of their own lives. We do not live any new fates, we do not perform any new deeds. All deeds have already been written in heaven and rest in our ancient brain.” In other words, Zvyagintsev’s cinema is neither more nor less than a repercussion of such already almost forgotten philosophical school as structuralism.

Alex, Vera, Kir and Eva climb a hill and find themselves in a wonderful grove which looks like Eden. There used to be a spring there. Water from the spring used to flow down a stream, pass under the house and rotate its millstone. It can be assumed that the spring, watercourse, and millstone used to animate the House of God. The spring dried up, however. Alex had seen water in this spring before, but Kir had not. Alex answers Kir’s question why the spring dried up, “God knows.” Thus, while Heavenly Eden used to give reviving water to the Church in the past, it does not give it any more, by the will of God. The parallelism between “dryness” in the Christian life and the life of modern family is obvious. Which is cause and which effect is not important. 19 minutes 37 seconds – 21 minutes 42 seconds The plot becomes more tense. This episode begins with a dialogue between Vera and Eva. Vera makes an apple and calls her daughter “bunny” or “sunshine.” Eva suddenly bristles: she does not want to be “sunshine” any more. She wants to be just “Eva.”

In other words, the New Woman Eva, also wants to find herself in her own independent feminine essence, just as the New Man, Mark, wants to find masculine independence. For Vera, Eva’s repudiation is a disaster. If this episode is viewed as a family story, Vera’s reaction looks unnatural and paradoxical. There is awe in her eyes. A mother cannot react to her daughter’s innocent caprice like that. Yet, The Banishment is not a game of daughter and mothers. The only possible explanation to her odd reaction is as follows: Eva repudiates Vera, repudiates her “solar” essence. In other words, Eva denudes Vera of her last hope, the hope to give herself to humankind. Because Kir and Alex are already estranged from Vera, and all her aspirations were only for Eva, the female half of humankind. Now all connections are broken. Now Vera needs some way out, some other opportunity; and she finds such an opportunity.

Vera tells Alex that she is pregnant but the child is not his. Thus, the baby, whose very being is questionable, becomes an opportunity for Vera to find salvation. This possible child is the ultimate manifestation of the conflict between Vera and Alex. Alex is shocked and crushed by his wife’s announcement. She makes futile attempts to have it out with him, and later offers a “metaphysical explanation” for the pregnancy, but this “explanation” requires a tremendous effort from the listener, and Alex is able neither understand nor even lend his ear to Vera.

The logic of Vera’s actions baffles not only Alex, but also the viewer. Her position seems unthinkable, inexplicable. As it will turn out, her position is almost absurd, but only at first. The famous maxim Credo quia absurdum est, or “I believe it because it is absurd” is a paraphrase of a fragment from the early Christian apologist Tertullian’s work De Carne Christi, where in polemic against the Gnostic Marcion he writes, “The Son of God was born: there is no shame, because it is shameful. And the Son of God died: it is wholly credible, because it is ridiculous. And, buried, He rose again: it is certain, because impossible.” Faith is absurd, but the ultimate foundations of Being and the laws of the universe are no less absurd, from our viewpoint. Yet, in spite of the fact that these laws seems unfathomable and absurd, they are still laws. They do not condescend to our everyday, ordinary consciousness. On the contrary, Man must rise to their heights. In the very same way the demand of Vera (faith) that Alex (Man) should accept her and (and his) child is irrational and inconceivable. To accept Vera, it is necessary to make an intellectual effort, make a leap over the abyss of misunderstanding. All the same, her demand is absolutely necessary, since Vera (faith) is an invaluable gift, a precondition of human existence. Alex cannot rise to the challenge of this demand. He leaves Vera. Black night falls.

On the country road Alex meets a car. A certain Max (“greatest” in Latin), the son of Georgy (“farmer” in Greek) is at the steering wheel. Max offers to give Alex a lift. Alex agrees. Max knows Alex well since he works as a postman (herald?) in the city, but Alex does not remember him. With Max, he reaches the same station at which they arrived not long ago. From there, he phones Mark and tells him that they should meet. Mark agrees. However, something hinders Alex. In spite of the fact that mysterious Max lends him his car, Alex does not reach the city. At the crossroads of times, at the border between the City of God and the City of Man, restless Alex chooses Vera. He stops the car at the boundary between a cultivated forest and a treeless area. Once again, night is succeeded by morning, and gloom by light. 30 minutes 57 seconds – 39 minutes 14 seconds Upon arriving home Alex behaves as if he wants to find reconciliation with Vera. Whenever Vera tries to start a conversation, however, Alex imposes silence upon her again. He is unable to listen to her. Her words are just unbearable for him. At this point a number of new characters become entangled in the plot. They communicate with Alex like relatives who have not seen him for ages, as though, not finding faith in Vera, Alex searches for it in his old family. First, he invites Victor’s family to his place for the evening, and then goes to visit Georgy. Georgy, a hoary old man, arrives in Alex’s place in a car and takes him with the children to his farm. When meeting crestfallen Alex, Georgy lights up with pleasure. It is apparent that Alex’s arrival is a great holiday for the old man. In the course of their conversation it is divulged that Alex has not been home for 12 years. His father longed for him “painfully” and died without having seen his grandchildren. For Gerogy, the departure of Mark and Alex is also a puzzle: “People lived. Everything’s fine, it seemed, and, out of the blue… You never know what is waiting for you.” Nevertheless, Georgy is filled with joy. There is a lot of wheat growing in the farm yard. Georgy introduces his visitor to a donkey and leads him to the mill as if opening up his world to Alex, trying to interest and entice him. The mill is located high, it seems as if it hovers in the skies.

In Luke, Chapter 15, Jesus tells the famous parable of the prodigal son to his apostles. In the story there is a father and his two sons. The younger son took half of the family fortune and left his father but spent all his money and, after many years of drudgery and suffering, returned home. He did not expect his father’s mercy, and returned simply because he did not want to die from hunger as his father had always had a lot of bread. Contrary to his expectations, his father displayed great joy instead of anger and presented him with sandals, a ring and a well-fed calf. It is apparent that the episode with Georgy is a rendering of the parable where the figures of the father and the son are transposed to several characters: Alex’s father and Georgy, on the one hand, and Alex, Mark and Kir, on the other hand. In the context of the movie the visit to Georgy’s farm can be construed as a heaven-sent opportunity for Alex: God opens his munificence to Man. God requires nothing of Man except for love, but Man remains deaf and proves himself incapable of accepting His gifts. Alex withdraws into himself and pays no attention to Georgy. He seeks salvation on his own, and sinks in the bog of the Fall still deeper. Therefore, not finding a Son in Alex, Georgy now turns this attention to Kir. (Note that for some reason Georgy ignores Eva).

John, Chapter 12 says, “Jesus, finding a young donkey, sat on it…”, and further on, “Fear not, daughter of Zion; behold, your King is coming, seated on a donkey’s colt.” In other words, in this episode Georgy acts as the Father in relation to both Alex and Kir; that is, encountering Alex’s incomprehension Georgy looks for a new Messiah in Kir. The mise-en-scène here, Georgy and Kir’s crossed hands, resembles the fragment of Michelangelo’s fresco Creation of Adam. God breathes life into the man by putting out his hand to man’s hand: dead clay comes to life owing to the divine touch. Adam is born at the moment when God’s hand (in the hypostasis of the Father) and Adam’s hand touch each other. ((Interestingly, 2007 saw the release of critically acclaimed Simple Things by Boris Popogrebsky, a film I love which also quotes the Creation of Adam.)) According to Christian apologetics, Adam is the prototype of Christ. While Adam was the first man of the Old Testament, Christ was the god-man of the New Testament. 39 minutes 14 seconds – 50 minutes 16 seconds The episode with the arrival of Victor’s family develops the theme of “salvation.” Alex makes another attempt to approach his wife, but Vera’s timid words infuriate him again and he strikes her a blow. I do not know what Zvyagintsev meant by this episode, but I would like to note that after Victor’s family arrives, misunderstanding separates not only Vera and Alex, but spreads between all male and female characters of the film. Just as Alex cannot understand Vera, Kir also cannot understand his sister Eva and Victor’s three daughters Flora, Faina and Frida. Victor is also unable to understand his own daughters.

The children start playing hide-and-seek, and at this moment it becomes apparent that, notwithstanding the supposedly general rules of the game, Victor’s daughters and Eva use other rules which are totally incomprehensible to Kir. Kir and Faina compete for who will be the first to run up to a tree. Kir is in fact first, but that means noting to his sister: “no, she is the first,” Eva states. Flora goes beyond the conventional limits of the game, finding herself in the garden, where Kir finds her. The children walk through the forest and have a relaxed conversation. In another episodes, Alex and Vera walk in the same forest, but in the opposite direction. What does this mean? Genesis 3:24 says, “So He drove out the man and He placed at the east of the garden of Eden Cherubims, and a flaming sword which turned every way, to keep the way of the tree of life.” Italian painter Masaccio’s painting The Expulsion represents Adam and Eve being expelled, moving from right to left. In Zvyagintsev’s film, Alex and Vera also walk “to the left,” which means to the east. But Flora and Kir, perhaps out of spite, walk from left to right or from the east to the west. Ignoring unnecessary right/left political insinuations, I will suppose that the walk of Kir and Flora is an antithesis to the “Expulsion” of Adam and Eve, a “Discovery of Paradise” of sorts.

Not only Vera, but all women in The Banishment behave very strangely. The climax of incomprehensibility is a strange conversation between Victor, Alex and Max. Victor remarks that something strange is happening, and he can only vaguely surmise what. Faina, Victor’s daughter, comes up to him. She does not want to play any more and says that she is bored. Suddenly she stands on her head. For her, this inverted state is almost natural; she can stand upside down for a whole hour. Victor remarks, “acquire three daughters and you may be sure that you’ve acquired three more wives.” When Victor tires to stand on his head, he falls over right away. At this point I would like to leave plot collisions for a minute and mention the unusual artistry of Leningrad actor Igor Sergeyev, who plays Victor. Typically, when speaking about The Banishment, reviewers note the powerful acting of Konstantin Lavronenko (Alex), Aleksandr Baluyev (Mark), and Maria Bonnevie (Vera). Lavronenko received the Best Actor Award at Cannes, but the supporting cast is also very good. I have always been impressed by films in which the supporting characters look like live people and not just a kind of biomass. In this respect, The Banishment is faultless. The girls from Victor’s family, Faina, Flora and Frida (Sveta Kashelkina, Elizabeth Danzinger and Yaroslava Nikolayeva, respectively) are real kiddies with infinite charm, and the acting of their father in the drinking scene deserves a special award.

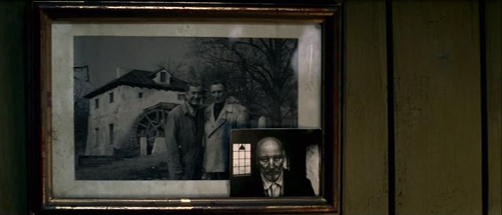

The role of “messenger” at this moment is taken by a rather inconspicuous character. While Alex, Victor and Max drink wine and talk about the incomprehensibility of women, in the kitchen the women talk about their children. Knowing nothing about the pregnancy, Victor’s wife Liza hints to Vera that a third child is desirable: “God loves Trinity.” The motif of Trinity is repeated in The Banishment many times: Victor has three daughters; Max, Alex and Victor have a three-way conversation; and it can be seen in old photographs in the house that Mark had three children. The film has three male protagonists: Alex, Mark, and Robert. And who is Liza (or Elizabeth), after all? Luke, Chapter 1 tells that the angel Gabriel appeared before the Virgin Mary with the message about the forthcoming birth of the Savior. Doubtful, the Virgin asked the angel, “How can this be, as I have not known a man?” And the angel answered, “The Holy Spirit will come upon you, and the power of the Highest will overshadow you,” and then in confirmation that “with God nothing will be impossible” mentioned Elizabeth as an example. Righteous Elizabeth is the mother of John the Baptist, the wife of priest Zacharias. According to the Apostle Luke, she is Mary’s cousin. Mary visits her pregnant cousin, and Elizabeth is the first to tell her about her upcoming fate. The Holy Virgin gives birth to the Savior and Elizabeth becomes the mother to John the Baptist. Both Mary and Elizabeth accept the will of God. The Mother of God’s words, “Behold the maidservant of the Lord! Let it be to me according to your word” became the moment of the Virgin Birth, and the Gabriel’s message became the Annunciation. The Annunciation has been regarded as the first act of redemption, in which the Virgin’s obedience counterbalances Eve’s disobedience. Mary becomes the “new Eve.” It is said God sent the Archangel with the Good News on the 25th of March, which is traditionally also the day of the Creation.

Thus, humankind was given the second chance. Similarly, a second chance is given to Alex’s family, but if the first divine message was sent to Alex through Georgy, now it is sent to Vera through Elizabeth. According to the logic of allegory, which goes in parallel to the outline of event, Liza is God’s messenger. 50 minutes 16 seconds – 01 hour 01 minute 22 seconds Not everything is so simple in the sublunar sphere. The telephone rings, and Alex learns that Mark is waiting for him at the railroad station. Alex has to leave the guests. He takes Kir with him. Eva also wants to go, but despite her pleas Alex leaves the daughter at home. On the way Kir tells Alex that in his absence Robert visited Vera… Robert visited Vera, that is that… At the station Alex tells Mark about the cares of the last day. He waits for advice. Mark listens to his brother with an acid look on his face. Like the Wandering Jew who has seen everything in the world, Mark gives quite an extraordinary piece of advice: “Whatever you do, everything will be right. If you want to kill, then kill. The gun is in commode at the top. And this will be right. If you want to forgive, then forgive. And this will be right too…” It is obvious that such an answer bewilders Alex. However, is Mark’s answer so paradoxical? Actually, Mark’s thoughts are nothing else but a paraphrase of the well-known thesis of the Greek sophist Protagoras: “Man is the measure of all things.” This slogan was brought back to life by the humanists of the Renaissance and taken up by Modernity. The concept of Man as the center of the Universe and the ideology of anthropocentric humanism built upon that concept have become the main trend for the modern society. Some people believe that Nietzsche’s philosophy became the acme of Protagoras’ maxim. In the 20th century this idea was attacked from very different positions, from religious fundamentalism to leftist politics. (In my opinion, the most subtle and ingenious criticism of anthropocentrism is found in Heidegger). There is no doubt at all that Mark is a parody of the anthropocentrism of the modern society. Mark behaves in Nietzsche’s Superman as the hero of the new time. He always finds the justification for his actions in himself. Sometimes his adamant stoicism becomes self-renunciation. Mark has forgotten his mother, father, wife and children. He has neither past nor future, but, notwithstanding the obvious pain of such renunciation, he finds a certain mysterious meaning in it. But this is not everything yet. Do you remember Kir’s words “about a strange odor in the house?” After the conversation with his brother Alex drives home, and on the way Kir explains the source of this odor: “Mark smells like inside the house.” Georgy previously said, by the way, that Mark had often visited the parental house. In Judaism, there is a mention of a certain Beelzebub, or Baal-Zebub, a demon borrowed by the Jews from the Babylonians. The name Beelzebub is translated as “the Lord of the Flies.” From Judaism Beelzebub passed to the New Testament and was mentioned in Matthew, Chapter 12. In the Babylonian tradition, animals associated with eating carrion, corpses, with uncleanness and dirt, including flies, belonged to Ahriman’s kingdom. Beelzebub was represented as a disgustful blowfly that flew over the corpse after a person’s death to take possession of his soul and befoul his body. The Jews also considered flies to be an unclean insect, one that must not appear in Solomon’s Temple. The character of Beelzebub often intersected another denizen of the lower world, Lucifer, the Fallen Angel of the Prince of Darkness. Among other signs of deviltry, it is traditionally mentioned that Satan can be identified by his sulfurous odor. According to Kir’s remarks, Mark has a strange, long-lasting odor. The Devil tried to tempt Christ with worldly goods, and Mark keeps offering various worldly goods to Alex: a car, money, and the weapon of power, a gun. So, what do we have as a result of this symbolism? Zvyagintsev goes so far in his rejection of anthropocentrism as to liken Mark not only to the Nietzschean Superman, but also to the Prince of Darkness himself. 01 hour 01 minute 22 seconds – 01 hour 08 minutes 37 seconds The subsequent developments can be interpreted as a “tug of war” for Alex between “the heavenly host and the earthly host.” The situation is very tricky. Alex constantly hesitates between Vera and his brother. Alex comes home from the station, and guests Georgy and Elizabeth call to him as if “by accident”: “Well, where else can you see such a sky!”

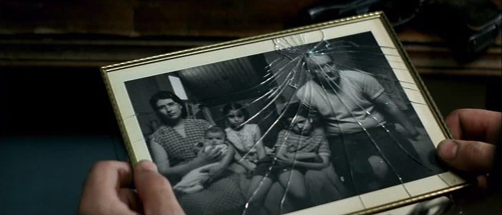

Alex makes another attempt to talk to Vera. He does not want to lose her. He wants to help her. In the last night her imploring touches and glances are directed to Alex. Early in the morning, when at the brother’s instigation Alex takes the gun from the commode upstairs, he sees a broken photo of Mark’s family—with his wife and THREE children.

The telephone rings. Alex picks up the receiver but instead of words he hears music. Flora played a record with a strange melody and put the receiver against the record player without saying anything. What does this mean? The piece is Bach’s Magnificat, a Catholic canticle to the text of the song praising of the Virgin Mary and the Annunciation. Alex looks at the children and says to his wife, “Well, Vera, please make breakfast for us. Let us eat together. Be their mother, and I’ll be their Father.” A smile lightens her face for the first time in a long time.

Nobody has noticed the strange fact: in these seconds Vera changes dresses at an awful speed. She gets up from the bed in a white dress, stands with Alex by the window in a blue dress, and comes out of the house in a red one! She heads for the exit in a blue dress, and outside she already wears a red one!

In Christianity white is a funeral symbol. In the Orthodox Church the burial service is performed by priests in white robes. Blue is the color of the sky, the color of heavenly Love. Red is a symbol of God’s ineffable love for the human race, the color of joy and the color of sacrifice. ((Strangely, in Ivan Vyrypayev’s Euphoria (2006) the main heroine is also named Vera, also lives on the margin of civilization in a lonely house, also has a dress that changes color from red to white, and is also sacrificed by a jealous husband. Other common elements are the style and color of dresses, and country bungalows, and 3 to 4 main characters. etc.)) Just when it seems that the heavenly host has won, a sudden turns happens. Alex comes out of the house with his family. They walk quite a long way from the house when the telephone rings. Alex comes back. 01 hour 08 minutes 37 seconds – 01 hour 19 minutes 28 seconds Alex picks up the receiver. The telephone is silent, but Alex finds out from the operator that the caller was Robert. Alex’s hesitations end at once: he makes a decision. From that moment on the events unfold at a dashing speed, and characters start falling into the abyss head over heels. For me, the feeling of black gloom, hopeless terror when one misfortune rolls over another, proved to be the most valuable thing in the movie. (By the way, this condensation of darkness has been dramatized quite faithfully. More than once I witnessed how in some families one death was followed by several others, how misfortunes turned into black holes that drew everything alive inside). The family ascends to the old cemetery to the nameless grave of the Father. Alex answers Kir’s question, “Granddad was as old as Georgy?” with “no, he was younger.” In the old family photographs we can see the “young” father who had been waiting for his sons for years! A contradiction is apparent. However, this contradiction is resolved if we recall that according to the canons of the Church, the Son and the Father have existed “since the world began.” The Trinity exists out of time. Eva’s question, “and why did he die?” is answered by Alex with “all people die”. So, “God is dead”?

Alex’s “youngish father” Vera understands that she is doomed. On the way to the churchyard the family, led by Alex, meets a flock of sheep. The flock is headed by a donkey. The family goes down to the Church but its doors are closed. It is impossible to enter. Upon coming back home Alex arranges with Victor to send the children to his place for some time. Everything is ready for the punishment of Vera.

The reflection of Vera in a black frame looks like a mourning photo Vera manages to phone Robert at the moment when Alex takes the children to Victor’s car. Robert is alarmed by Vera’s call, but she cannot tell him about her trouble. This is a very significant moment in the plot. In her last call, Vera apparently waits from Robert for something more than just a Question. She waits, but receives nothing. What does Vera wait for? We find out at the end of the film. When they are left alone, Alex and Vera walk to the forest where Vera tells about her readiness to implement Alex’s will. 01 hour 19 minutes 28 seconds – 01 hour 32 minutes 01 second Alex phones Mark and tells him about his decision. Mark arrives with two doctors at dusk. As the children of Alex and Victor are solving a jigsaw puzzle (da Vinci’s The Annunciation) and Frida is reading an excerpt about love from Corinthians, Vera is dying in Alex’s house. The abortion looks like a ritual killing. The doctors wear black clothes like angels of death.

The house stands in pitch-black darkness. Vera makes no sound, though she cannot stand the pain. Nevertheless, the doctors say that it is normal, that Vera is “going to sleep.” Mark echoes, “and this is right.” These words play on the state of faith in the modern civilization, where the silence of religion is the condition of its existence.

Vera remains silent, and Alex becomes anxious. He comes in her room every minute, anticipating something bad. Realizing his fault Alex begins to repent. He whispers, “help me Vera”, but Vera will no longer make any sound. Finally, Mark too realizes that something wrong has happened. Instead of the ambulance service he phones his friend German, a local doctor. Mark assures his brother that German “will be here soon.” Soon or not, judge for yourself. Here's Mark calling.

And here comes German.

01 hour 32 minutes 01 second – 01 hour 59 minutes 29 seconds German arrives and pronounces Vera dead. He tells Mark delicately, but Alex understands everything at once. Alex is shaken. His grief turns into exasperation. He dashes onto Mark, but Mark copes with him easily. Expectedly, German is also dressed in black. It seems as if Zvyagintsev is scoffing at doctors. Every medical intervention in the film ends up in death, and every ambulance becomes a hearse. Medicine here acts as an allegory for a purely scientific understanding of man, with all the ensuing consequences. Alex calms down. In spite of his shock, Mark, with maniacal persistence, aims to bury Vera, no matter what. I am not sure whether this mise-en-scène with Mark and Alex, where a cross can be seen again in the window and a poker bends under it like the Serpent, can be construed as another metaphor. Maybe it is a coincidence.

The ambulance brings Vera’s body to the city morgue, where Mark and Alex soon find themselves. Only Alex expresses a desire to see Vera for the last time. Mark, despite the distress of his soul, does not want to see her, but appeals to Alex again to bury Vera. A man of action, Mark does not rake over the dust and ashes of the past, looking for the cause. One should live on, one should think not of what has been done, but of what must be done. The traditional priority of Western culture, of Business over Idea, is played on here. Alex and Mark go back to the house, where Mark has a heart attack. German arrives again. In the course of the conversation between German and Mark it turns out that the real cause of the death was a soporific Vera took: in other words, soporific, sleep, silence of faith is her death. This news discourages Mark. We have noted that the infernal image of Mark is a parody of the concept of the modern man, the Superman, but it should be said that Mark is not only the executioner, but also the victim: the victim of himself. He also has faith, but his faith in science, action and self-sufficiency suffers a crushing defeat in the film. Mark is tormented, but all his actions only aggravate his adversity. It is he who becomes the catalyst of the disaster, it he who invites the “abortion mongers,” criminally mitigates his brother’s apprehensions, and it is he who delays the arrival of the doctor. Even after the abortion Vera could have survived, but Mark did everything so that it did not happen. German tells Alex that Mark is seriously ill. Vera’s funeral should take place the next morning. German wants to stop Mark again, but Mark is irrepressible. He asks German to give him a potent stimulant, for at least three hours. Before long the brothers, with grave diggers, and a priest bury Vera at the same graveyard where she stood only the day before yesterday. After the funeral the priest walks down to the temple, walks for a very long time, walks down a straight track. There is another track that twists to this temple… you do not need to be seminarian to recognize this textbook parable about the roads to God. Two different roads lead to God: a straight one and a curved one. The church goes to God along the straight road, but the way along the curved road is also possible. But it more difficult, and longer.

Alex comes back home by himself with dead Mark on the back seat of the car. As soon as Vera was buried, the “Superman” also passed away. This is the message of the film: Man cannot exist without Faith. Having kicked Faith out, having thrown it out of one’s life, having destroyed the memory of it, having remained alone face-to-face with oneself and having buried Faith, Man is doomed to die. Alex assigns responsibility for Mark’s funeral to German and goes upstairs. He takes the gun and money out of the commode. There is not a trace of his former hesitancy. After losing Vera Alex has acquired determination. Now he knows for sure what he wants. He drives to the city and waits for Robert. While waiting he falls asleep, and images of tree tops suddenly appear on the car’s surface. The reflection of trees in the city where there isn’t a single tree!

Reviewers interpret this episode differently. Some write that all subsequent developments are Alex’s dream. Others believe that Alex’s dream ends when Robert arrives. Whether in a dream or not, German, the man in black, closes the shutters of the house. His silhouette completely obstructs the window opening, and along with it the cross, which used to be seen from everywhere. Raindrops fall onto dry ground. The reviving water fills the stream and flows to the millstone of Alex’s family home. Robert comes, awakens Alex, and invites him into his place. Alex comes in, sits down and puts the gun on the table. It seems that the punishment is inevitable, that the retaliation will be performed. But at this moment the telephone rings. How many times now? Robert picks up the receiver: it is Vera calling. The plot folds back upon itself and draws the viewer with it. Alex and Robert walk along the corridors of memory, back to the time when Vera was alive and the sky was so blue… 01 hour 59 minutes 29 seconds – The end The last part of the film is the story of Robert saving Vera. Robert does everything in a different way, not in the way that Alex, Mark, or even he himself acted in the story of Vera’s death. He does everything the other way around. We remember that Vera’s last telephone call before her death was to Robert. Then, he left Vera alone with herself, but now he comes dashing to dying Vera’s call and does everything he can. If Mark and the doctors wanted to send her to sleep, Robert repeats the words “just don’t sleep, Vera!” like a prayer. He gives Vera water, causes her to vomit the poison, he talks to her, he listens to her. If in the story of death it always rains in the city, in the story of salvation, after the rain the sun shines for the first time. When Max, God’s messenger, rides his bicycle, there is sky blue reflected in the puddles on asphalt. Max rides up to the door of Vera and Alex’s city house. He delivers the letter with the pregnancy test. In the mise-en-scène of the letter delivery, the mysterious postman Max does what Stirlitz would call an “exposure.” Before handing the message to Vera, Max carelessly lets it fall and then drops on his knee in the very same manner as the kneeling Archangel Gabriel does in numerous representations of the Annunciation scene. If we look at Sandro Botticelli’s painting of the same name, everything clicks into place. Now we can understand Max’s story about working as a postman, about the Father who had sent him to the city “to stretch his wings,” and about the addressee.

The next day Robert calls Vera again, and once more prevents her from sleeping. When Vera hesitates, Robert goes to her himself. Robert and Vera go for a walk around the morning city along the channel, on the other side of which the colossus of a black factory can be seen. In the previous story, flocks of sheep grazed near the house, but in the alternative history there is gigantic graffiti on the factory depicting the struggle of the working class. There by the channel Robert tells Vera the story about the keys from the house, which he lost and then found at the bottom of a glass, when he had a drink and remembered where they were. Where Alex spends several days in tormenting reflections, Robert just came in and had a drink. Vera says that she has never lost keys, and Robert notes that everything is still to come for her. These words injure Vera, and she goes back to her place. Vera asks Robert to stay, in spite of the dubiousness of his position, and he stays with her to the very end. At this moment Vera begins to show old photos. The reminiscences about the happy past injure her still more, as in the present everything is different. The film draws to an end. Finally, Vera tells Robert about her pregnancy: she carries Alex’s child. What is the reason for her torment? We remember that during the conversation between German and Mark a suspicion appeared that Vera was not pregnant. After the conversation with Robert, however, Vera states openly that she carries a child. Alex’s child! Why on earth should she kill herself? Vera’s answer has frightened away, repelled the audience from Andrei Zvyagintsev’s second feature. The view can be understood, as the viewer has just watched a movie about family drama, and Vera’s answer destructed the plot structure at a stroke. In The Return Zvyagintsev enfolded a philosophical parable in a worldly story. In The Banishment, he sacrificed a worldly story for the sake of philosophical profoundness of the statement. Actually, the essence is common to both The Return and The Banishment. The audience did not understand and did not forgive the director. It is a thousand pities, because Vera’s answer deserves consideration. So, Vera openly states that she carries a child. Alex’s child. Where is the truth? Both. Vera died and stayed alive at the same time. This is as simple and true as the fact that our children are not only our children, and we are not only the children of our parents. This is as true as the fact that the boy or girl whom we see on old photographs and say “this is me” in reality is not actually me any more. This is as true as the fact that we can live without ever dying, although we die. But we can live forever only together, and only when we have Faith. Alex returns; he returns to the place from whence his elder brother arrived at the beginning of the film. He drives along the same road, past the same tree. Now he is calm and he knows what to do. Alex returns to his children. Epilogue Films similar to The Banishment are vanishingly few.Every year several thousands “simple” movies are released which require no effort form the viewer, which you can watch and enjoy; but there are very few directors who climb to such heights and require the same from the viewer. That is why accusations against Zvyagintsev of “mannerism” and of a broken plot are absurd. Actually, there is no broken plot, and the mannerism—or rather otherworldliness—is quite precise and the right entourage for such content. Some may ask, why should we climb to such heights? Why do people fly to the Moon, play football or climb Everest? They just want to, and they climb; many people have an ineradicable need to deal with problems of a universal scale, and nothing can be done about it. It can only be prohibited. In 1901 H.G. Wells wrote a story entitled “The New Accelerator.” Its protagonist, Professor Gibbern, invented a preparation which increased the perception of the speed of reality a thousand times. After the Professor and the narrator had tested the preparation on themselves, reality appeared before them in another light. A bee turned into a snail, a coquettish wink into an ugly grimace, and a wonderful tune into a death rattle. The problem of Zvyagintsev’s cinema, or rather the problem of its perception, is not a problem of erudition, taste or level of education. The problem is the speed of perception. The modern human being is like the person in Wells’ story. To him, the plot line seem a motionless still life, a dumb show. The main thing here is not to hurry, not to hasten. Not to hurry to a trolleybus, fitness center, to a flight to Athens, and not to hurry to write a weekly review for the Art column. Eugene Vasiliev |